"The following is a brief sketch of prison life at Elmira, New York, written by Sergeant G. W. D. Porter, 44th Tenn. Infantry Regiment, CSA. Sergeant Porter adds another bit of information to the already voluminous record of the treatment of Confederate prisoners. In contrast with the conduct of Colt, Beale and the hog-backed Scotcbman, it affords us real pleasure to record in these pages the kindness and gentlemanly demeanor of Lieutenant Groves, the cashier of the prison." Dr. Edwin L. Drake, Editor "The Annals of the Army of Tennessee"

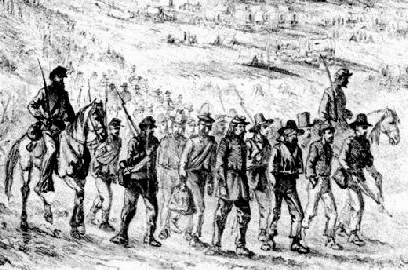

The writer, with about five hundred other prisoners of war, arrived at Elmira about the first of August, 1864, after a confinement of forty five days at Point Lookout. I spent the first day in a thorough examination of my new abode, and its advantages as a home until fortune would release me from its durance. It contained several acres of ground, enclosed by a plank fence about fourteen feet high; some three feet from the top on the outside ran a narrow footway, or parapet, of plank, supported by braces. On this the sentinels walked day and night, being enabled from this height to command a view of the entire prison.

|

|

The south, or rear, line of the enclosure stood on the bank of the Chemung. Through the center ran a deep channel, cut by the river at high tide, the upper and lower ends of which were dry part of the year; the middle always contained water to the depth of two feet or more. During, the hot months, the prisoners suffered greatly from heat at night, owing to their crowding in tents. In October, materials and tools were furnished, and wooden barracks were built. During our tent life, two blankets were furnished to six men; one stick of green pine or hemlock, from four to six feet long and rarely over six inches in diameter, was the daily allowance of fuel for six men; no tools were allowed to cut and split it. J. W. Daniel was woodchopper for our mess, patiently hacking the wood in two with an old case knife, and splitting it with the aid of a railroad spike and a rock. The routine of roll-call was most exactingly carried out in spite of bad weather, no one being allowed to break ranks under the most urgent circumstances until the signal was given. Owing to the diet, crowding and other unwholesome surroundings, bowel complaints were exceedingly common and severe, and the requirements of the disease often subjected the unfortunates to a brutish befouling of clothing and person while standing in ranks awaiting the leisurely completion of a simple routine task.

Majors Colt and Beale were at times not only unkind, but unjust and oppressive. Beale, on one occasion, aroused all of the inmates of the prison on a bitter cold night, and made them stand in line until he ascertained how many had United States overcoats, and where they got them. He then had the coats carried to his quarters, where the tails were cut off, and the mutilated garments restored to their owners. These officers had men tied up by the thumbs to make them reveal suppositious plots. An instrument of torture called the "sweat box " will bear describing to the uninitiated. They were made of stout planks, of different dimensions, so as to gauge the victim's size. They were secured upright to a post, with a hinged door, and when a culprit could be squeezed in, so much the better for the violated law. An aperture for the nose was the only evidence of charity in their construction. When a prisoner was to be committed, he was marched to successive boxes until one was found to suit; with his back to the entrance and his arms close to his side, he was thrust in and the door closed with a push and fastened.

Ward inspection was held every Sunday morning by a captain or lieutenant. On these occasions none were excused from attendance. The presence of every man had to be verified; and if any were found in the privies, or on the road therefrom, they were dragged to the guard-house, where a mysterious performance added terror to the situation. The guard-house had two rooms-the rear one for prisoners; as the victim entered the.door a blanket was dropped over his head: and he was forced to the floor and robbed of every thing he had. He was then left half-suffocated, without an opportunity of knowing who did the deed. Many of the Federal officers were brutes in the human form. One, whose name I have forgotten, was a fiend. He was a tall, humped-back Scotchman, nicknamed by the boys "Old HogBack," but he was a hog all over. On several occasions I have seen him kick sick men off of the walk with his heavy boots, simply because they were too feeble to get out of his way quickly enough, or did not care to get out in the mud and water to let him pass. I hope some reader of the ANNALS may, perchance, remember his name and report it, so as to impale his memory with the infamy of wanton cruelty to helpless and defenseless fellow-creatures.

Lieutenant Groves, the cashier of the prison bank, was, in every respect, a gentleman, and, for his kindness and humanity, his name is gratefully remembered by every inmate of the Elmira Prison who come in contact with him.

Threats of retaliation for the Fort Pillow affair were often circulated to induce men to take the oath. At one time, it was put out that lots were to be drawn for men to be placed on gunboats under fire of Sumter and other forts. To an officer who was threatening me with such terrors, I replied: "Put me down on that list as a volunteer. I would be delighted with the exchange, and think I can stand any thing your men can." I was determined to brag a little, just to cut his feathers, and I succeeded.

My gorge, bile, spleen and phlegm will rise somewhat yet at the recollection of the quantity and quality of the food doled out at the model humanitarium at Elmira in the years 1864-5. I have long since gotten over the sense of soreness begotten of the knocks and hurts incident to honorable warfare; but Elmira, somehow, when I happen to think of it, will play the deuce with my patriotism and loyalty to my country in thought, not act, but only at these times. Ah well! I'd live it down and die content if I was only sure that "Old Hog-Back " will not be able to cbeat the devil out of his own. Prove me this, and I am "truly loyal." But here's the ration: The strong sustained life on four ounces of sour light bread and three ounces of salt beef or pork for breakfast; for dinner, the same amount of bread was allowed, and, in lieu of the meat, a compound called soup, but in reality nothing more than hot salty water, in which bags of peas or beans had been boiled, but which were carefully removed and kept for other uses than to make animal heat for cold, starving prisoners of war. This salt-water diet will account for the large number of cases of scurvy and dysentery which carried off so many. A great number of the men were in rags, and but a small quantity of clothing was issued by the United States Government. Of that received from home and friends, the amount was restricted, and only obtainable on a permit approved at headquarters. When the mercury got down to 35 degrees below zero in the winter of 1864-5, I saw numbers of my comrades with frost-bitten hands, feet, ears and faces.

For the truth of these statements, I am willing to abide by the evidence of hundreds of living witnesses North and South. Moore, Colt and Beal, of the prison authorities, could tell a tale if they would. They surely can remember an order that was to deprive a prison full of half -starved wretches of all food until they produced a barrel of beans which had been stolen by their own underlings. They can recall the fact that only one stove was allowed to each hundred men, and only half enough fuel for use, while hundreds of wagon-loads were stacked on the premises. But the graves of dead Southern soldiers at Elmira tell a tale, before which every utterance of the lip or pen is dumb in comparison. The writer, with about five hundred other prisoners of war, arrived at Elmira about the first of August, 1864, after a confinement of forty five days at Point Lookout. I spent the first day in a thorough examination of my new abode, and its advantages as a home until fortune would release me from its durance. It contained several acres of ground, enclosed by a plank fence about fourteen feet high; some three feet from the top on the outside ran a narrow footway, or parapet, of plank, supported by braces. On this the sentinels walked day and night, being enabled from this height to command a view of the entire prison. On the inside, large globe lamps were ranged at regular intervals, which were lighted shortly after sunset and extinguished after fair day-light, thus rendering it impossible, even in the darkest night, for anyone to approach without being discovered. Near the center of the enclosure, and on the north side, was the main entrance, by large folding doors. East of this point, on the outside about fifty yards from the enclosure, was a large observatory, upon which hundreds would crowd daily to get a view of the prisoners-many to gloat, perhaps, on their sufferings; some to gaze in wonder and awe upon the ragged, bob-tailed crew who had on many fields conquered their best armies; and some, no doubt, to sigh for an exchange of these men for fathers, sons and brothers who were suffering kindred miseries at Libby, Salisbury and Andersonville. A single tree -a walnut- stood opposite the observatory, and its shade was particularly grateful during the month of August.

The south, or rear, line of the enclosure stood on the bank of the Chemung. Through the center ran a deep channel, cut by the river at high tide, the upper and lower ends of which were dry part of the year; the middle always contained water to the depth of two feet or more. During, the hot months, the prisoners suffered greatly from heat at night, owing to their crowding in tents. In October, materials and tools were furnished, and wooden barracks were built. During our tent life, two blankets were furnished to six men; one stick of green pine or hemlock, from four to six feet long and rarely over six inches in diameter, was the daily allowance of fuel for six men; no tools were allowed to cut and split it. J. W. Daniel was woodchopper for our mess, patiently hacking the wood in two with an old case knife, and splitting it with the aid of a railroad spike and a rock. The routine of roll-call was most exactingly carried out in spite of bad weather, no one being allowed to break ranks under the most urgent circumstances until the signal was given. Owing to the diet, crowding and other unwholesome surroundings, bowel complaints were exceedingly common and severe, and the requirements of the disease often subjected the unfortunates to a brutish befouling of clothing and person while standing in ranks awaiting the leisurely completion of a simple routine task.

Majors Colt and Beale were at times not only unkind, but unjust and oppressive. Beale, on one occasion, aroused all of the inmates of the prison on a bitter cold night, and made them stand in line until he ascertained how many had United States overcoats, and where they got them. He then had the coats carried to his quarters, where the tails were cut off, and the mutilated garments restored to their owners. These officers had men tied up by the thumbs to make them reveal suppositious plots. An instrument of torture called the "sweat box " will bear describing to the uninitiated. They were made of stout planks, of different dimensions, so as to gauge the victim's size. They were secured upright to a post, with a hinged door, and when a culprit could be squeezed in, so much the better for the violated law. An aperture for the nose was the only evidence of charity in their construction. When a prisoner was to be committed, he was marched to successive boxes until one was found to suit; with his back to the entrance and his arms close to his side, he was thrust in and the door closed with a push and fastened.

Ward inspection was held every Sunday morning by a captain or lieutenant. On these occasions none were excused from attendance. The presence of every man had to be verified; and if any were found in the privies, or on the road therefrom, they were dragged to the guard-house, where a mysterious performance added terror to the situation. The guard-house had two rooms-the rear one for prisoners; as the victim entered the.door a blanket was dropped over his head: and he was forced to the floor and robbed of every thing he had. He was then left half-suffocated, without an opportunity of knowing who did the deed. Many of the Federal officers were brutes in the human form. One, whose name I have forgotten, was a fiend. He was a tall, humped-back Scotchman, nicknamed by the boys "Old HogBack," but he was a hog all over. On several occasions I have seen him kick sick men off of the walk with his heavy boots, simply because they were too feeble to get out of his way quickly enough, or did not care to get out in the mud and water to let him pass. I hope some reader of the ANNALS may, perchance, remember his name and report it, so as to impale his memory with the infamy of wanton cruelty to helpless and defenseless fellow-creatures.

Lieutenant Groves, the cashier of the prison bank, was, in every respect, a gentleman, and, for his kindness and humanity, his name is gratefully remembered by every inmate of the Elmira Prison who come in contact with him.

Threats of retaliation for the Fort Pillow affair were often circulated to induce men to take the oath. At one time, it was put out that lots were to be drawn for men to be placed on gunboats under fire of Sumter and other forts. To an officer who was threatening me with such terrors, I replied: "Put me down on that list as a volunteer. I would be delighted with the exchange, and think I can stand any thing your men can." I was determined to brag a little, just to cut his feathers, and I succeeded.

My gorge, bile, spleen and phlegm will rise somewhat yet at the recollection of the quantity and quality of the food doled out at the model humanitarium at Elmira in the years 1864-5. I have long since gotten over the sense of soreness begotten of the knocks and hurts incident to honorable warfare; but Elmira, somehow, when I happen to think of it, will play the deuce with my patriotism and loyalty to my country in thought, not act, but only at these times. Ah well! I'd live it down and die content if I was only sure that "Old Hog-Back " will not be able to beat the devil out of his own. Prove me this, and I am "truly loyal." But here's the ration: The strong sustained life on four ounces of sour light bread and three ounces of salt beef or pork for breakfast; for dinner, the same amount of bread was allowed, and, in lieu of the meat, a compound called soup, but in reality nothing more than hot salty water, in which bags of peas or beans had been boiled, but which were carefully removed and kept for other uses than to make animal heat for cold, starving prisoners of war. This salt-water diet will account for the large number of cases of scurvy and dysentery which carried off so many. A great number of the men were in rags, and but a small quantity of clothing was issued by the United States Government. Of that received from home and friends, the amount was restricted, and only obtainable on a permit approved at headquarters. When the mercury got down to 35 degrees below zero in the winter of 1864-5, I saw numbers of my comrades with frost-bitten hands, feet, ears and faces.

For the truth of these statements, I am willing to abide by the

evidence of hundreds of living witnesses North and South. Moore, Colt

and Beal, of the prison authorities, could tell a tale if they would.

They surely can remember an order that was to deprive a prison full of

half -starved wretches of all food until they produced a barrel of

beans which had been stolen by their own underlings. They can recall

the fact that only one stove was allowed to each hundred men, and only

half enough fuel for use, while hundreds of wagon-loads were stacked

on the premises. But the graves of dead Southern soldiers at Elmira

tell a tale, before which every utterance of the lip or pen is dumb in

comparison.